On a flight from Newark to the West Coast not long ago, Jeff Jarvis, author of the book “What Would Google Do?” fell into a conversation with a fellow passenger familiar with his work. But it was not a face-to-face chat. Rather, it started as an exchange of Twitter posts at the boarding gate.

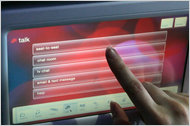

Virgin America also offers seat-to-seat messaging via video screens installed on seat backs.

When the plane landed, Mr. Jarvis recalled, the conversation resumed. “It was as if someone had recognized you and come up to say, ‘hello,’ on the flight.” He said it reminded him of the days when passengers could socialize in airborne lounges, “except now it’s happening digitally.”

The mobile phone and laptop are not just tools to stay in touch with the office or home anymore. As Mr. Jarvis can attest, a growing number of frequent fliers are using their mobile devices to create an informal travelers’ community in airports and aloft.

Airlines and social media providers are scrambling to catch up. Airlines are beefing up their presence on networking channels, and travelers’ groups like FlyerTalk.com have created new applications that allow members to find one another while on the road. Business travelers can use these services to share cabs to the airport, swap advice or locate colleagues in the same city. As Mr. Jarvis puts it, “finding a like-minded person to travel with lessens the chance of getting stuck next to some talkative bozo” on a long flight.

Increasing availability of Wi-Fi at airports and on planes has made the travel networking possible. A survey of 84 of the world’s largest airports by the Airports Council International earlier this year found that 96 percent offered Wi-Fi connections, and 73 percent had connections throughout their terminals. About 45 percent offer the service free; the rest charge an average of about $8 an hour.

More than 10 airlines in North America, including American, Delta and Southwest, are wiring their planes for Internet access, and major foreign airlines like Lufthansa are introducing new technology that will let customers connect on transoceanic flights. In-flight calls are still forbidden on most flights, although several airlines, including Emirates, have been testing calling on shorter trips.

As many as 1,200 commercial airliners in the United States will have Wi-Fi capability by the end of the year, according to Chris Babb, senior product manager of in-flight entertainment for Delta Air Lines. “It’s a much different world than it was a year ago,” he said, noting that on a recent flight he exchanged e-mail messages with several colleagues who were in the air at the same time.

And Virgin America, which has wired its entire 28-plane fleet for the Internet, said about half of its passengers brought their laptops with them and 17 to 20 percent were online at any given time. On longer flights, about a third of passengers go online. Like airports, most airlines charge a fee for the service, usually ranging from $5 to $13.

Some airline passengers may mourn the loss of their last remaining refuge from e-mail intrusions. But the benefits of staying connected became clear several months ago during the eruption of the Icelandic volcano that grounded thousands of European flights. Facebook and Twitter set up sites for stranded travelers, who swapped ideas and offered rides to ferry terminals, and Twitter had its own thread. Based on anecdotal reports, the sites helped in getting information out quickly.

For those with time at an airport, FlyerTalk.com has an “itineraries” feature that allows travelers to post their coming flights in the hope that other “flier talkers,” as they call themselves, may be heading the same way.

Lufthansa said it consulted with FlyerTalk members in developing its own product to help customers tap into social networking from any location. The application works on iPhones and this fall will be available on BlackBerrys. A built-in GPS allows users to find fellow fliers who might be nearby. It also has a taxi-sharing feature that travelers can activate upon landing.

Users must already be members of the airlines’ loyalty program, and Lufthansa said it had added privacy controls for those who preferred to travel incognito. FlyerTalk’s president, Gary Leff, said that while some members had welcomed the service, others were skeptical. “Some of us just like to keep to ourselves” on the road, he said.

For those who want to connect, few airlines can match Virgin America for mingling opportunities. In addition to its Internet service, it offers seat-to-seat messaging via its seatback video screens. It has also teamed up with match.com to create a party atmosphere on specific flights (reportedly at least one couple who met this way became engaged). But there is also the potential for spurned advances and hurt feelings.

“Seat-to-seat chatting could lead to a negative form of social networking,” said Jeanne Martinet, a social commentator who writes the missmingle.com blog. “What if someone spots another passenger doing something annoying?” she asked. In the past, that person might have simply suffered in silence. Now, Ms. Martinet said, “It would be tempting to message them, ‘Can’t you get your big feet out of the aisle?’ ”

Porter Gale, Virgin’s vice president of marketing, said there were safeguards against abuse and that a passenger could simply turn off the messaging function. And she said that offering Wi-Fi access had benefits for the airline, like the ability to resolve a customer’s problem before a flight lands.

A passenger once sent an e-mail message to the airline from his seat, saying that he was not pleased with the sandwich he had just eaten, she said. A customer service representative on the ground sent a message back to the plane, and shortly thereafter, she said, the passenger was served an acceptable substitute.

This can work against the airline, too, as Virgin discovered when a New York-bound flight was diverted and some passengers sent out messages venting their annoyance with the delay.